Some background info:

The film format “Cinerama” had guided the film industry into wide screen presentations. Studio executives ran for the doors after seeing Cinerama’s premiere in New York. Representatives of 20th Century Fox and Warner Bros. literally raced to France to meet with Prof. Henri Chrétien, the inventor of a filming process that he called Anamorphoscope. The rumor says Fox won the race over Warners by just a few hours. Chrétien had developed and patented his process in the late 1920’s. Efforts to interest not only his native French but foreign film makers in his widescreen process had been unfruitful for over 25 years. In fact, his patents had expired. So why were two major studios keenly interested in negotiating with Chrétien? The answer is simple, they needed the lenses that Chrétien had built. Those lenses, the Hypergonar, were the basis for the primary surge into true widescreen feature film making. So one could argue that Chrétien is the father of cinemascope widescreen.

Chrétien’s hypergonar lenses were based on an optical “trick” he called anamorphosis, in which an image contains a distortion that is removed with a complementary viewer. In the case of Chrétien’s lenses, a horizontal squeeze of 100% was imparted into the image on film resulting in a picture twice as wide as an image taken and projected through conventional lenses. In addition to the anamorphic adapters being used on the motion picture camera, a similar lens on the projector was required to expand the squeezed image on the cinema screen. At left: A original set of lenses circa 1927. The square lens in the foreground was mounted in front of a conventional 50mm camera lens, providing a 2x horizontal squeeze to the image. The projection lens behind it is the anamorphic adapter attached to the standard projector lens.

20th Century Fox secured world rights to Anamorphoscope, (with the exception of France and its possessions) and Chrétien’s small inventory of lenses. They immediately put them to use in Hollywood by resuming pre-production on “The Robe”, which had been halted while the old Chrétien lenses were being evaluated. When the film finally went before the cameras it was simultaneously shot in the standard Academy format for release in theatres not equipped for anamorphic projection in addition to the anamorphic lenses, though the resounding popularity of both CinemaScope and The Robe made it unnecessary for the standard version ever to be shown in a theatre. The size of the original anamorphic adapters limited photography to the use of only 50mm and longer prime lenses. Fox presented Chrétien’s company, S.T.O.P., with a contract to build and ship additional lenses. There appears to have been delays and quality problems associated with the new lenses. So Fox turned to Bausch & Lomb optical company to produce additional anamorphic adapter lenses based on Chrétien’s designs.

Even while shooting The Robe, Fox demonstrated their process to the other motion picture studios. Darryl F. Zanuck announced that 20th Century Fox would produce all future films in the new process and invited the other studios to license its use on their productions. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer immediately climbed aboard the bandwagon as did Walt Disney. Shortly Warner Bros., Universal, and Columbia decided to also use this new, and as yet unproven, process in major productions. Paramount declined and began work on VistaVision. RKO passed for the time being, as did Republic. Several independent producers also announced plans to shoot some of their planned productions in CinemaScope. Even before the first CinemaScope feature film premiered before paying audiences the success of the system was insured for the next several years.

No other technical advance in the history of motion pictures, including sound and color, gained such a high degree of acceptance among American film makers in such a short period of time. Film makers in the U.K. and the European continent were a bit slower to adopt CinemaScope as a mainstream technical advancement, for valid economic reasons following an economically devastating World War, but it wasn’t long before the new stretched image became popular despite the costs associated with production and presentation.

Chrétien’s company, S.T.O.P., worked to improve their own manufacturing capability after being granted the right to use the CinemaScope trademark in France and its possessions. This appears to be design “B”. More modifications were to come just as Bausch & Lomb and other optics companies refined their own designs and manufacturing techniques used to produce anamrophic lenses for both photography and projection.

“S.T.O.P.” short for “SOCIETÉ TECHNIQUE OPTIQUE de PRECISION.” Was the official manufacturer of CinemaScope camera and projection optics for France and their colonies. The significance of that arrangement insured that France’s other major early 1950s contribution to the motion picture, Brigitte Bardot, was filmed in CinemaScope with S.T.O.P. lenses.

Above some examples of French CinemaScope films featuring the Birgitte Bardot. Bardot also did some VistaVision films, typically French-British co-productions made by Rank.

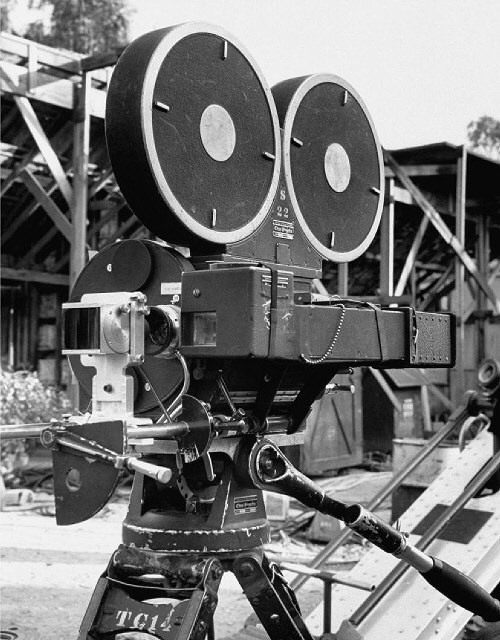

- The Chrétien made CinemaScope anamorphic lens used to photograph The Robe is seen mounted on a Fox Simplex silent camera. In this picture the lens is shown positioned slightly away from the Baltar prime camera lens. But when in use the anamorphic adapter is slid right up to the Baltar to preclude any light shining in between the two optics which could kill image contrast and potentially ruin a shot. The specifications for the picture was measuring 2.66:1, using the full 35mm silent aperture, and the sound would be 3-track interlock stereo. Everything that made up the motion picture theatre was going to have to be changed out. Fox’s engineers and their suppliers did everything possible to make CinemaScope backwards compatible with the technology that had been the standard since the late 1920s.

Above left, a Fox camera is pictured with the Bausch & Lomb anamorphic adapter lens, which incorporated significant improvements on Chrétien’s original design. To its right is the same camera fitted with a 50mm B&L combination anamorphic lens which allowed simultaneous focusing of the anamorphic and spherical elements, reduced distortion, transmitted more light, and were available in a wider range of focal lengths than what could be used with the adapter.

While preparations for production on THE ROBE progressed, the studio had not yet finalized all aspects of their new process, dubbed CinemaScope. The word “Cinemascope” was already a registered trademark for a video product. But an expenditure of $50,000 bought the name for 20th Century-Fox. Initial plans, and photography on THE ROBE, consisted of returning to the original full frame 1.33:1 silent camera aperture, which would provide a projected image with an extremely wide 2.66:1 screen ratio. Sound, like Cinerama, would be carried on a separate 35mm magnetic film synchronized with the picture projector. The stereophonic sound consisted of three channels behind the new wide screen and a forth channel fed speakers on the side walls and rear of the auditorium. By the time The ROBE was ready to premiere, the system had been altered to include the sound on the picture film in the form of four magnetic stripes, two located on either side of the picture and two outside the new reduced width sprocket holes, (which were dubbed “Fox Holes”). The magnetic sound striping on many CinemaScope and other widescreen formats was done by Reeves Soundcraft, owned by Hazard Reeves, the man responsible for Cinerama’s impressive stereophonic sound system. As a touch of irony, Reeves, then president of Cinerama, Inc. as well as his other ventures, was awarded a technical Oscar for the development of the magnetic striping used on CinemaScope films. He did not receive an Academy Award for his substantial involvement with Cinerama. While a good many companies competed with Reeves to produce magnetic sound stripes on films, Reeves’ process had the unique advantage of having the stripes actually stay on the film.

Peering into an anamorphic lens shows that it magnifies (projection lenses), or compresses (camera lenses) the image only in one direction. While all the elements in this Bausch & Lomb CinemaScope projection lens are round, they appear more and more elliptical as light passes through one element to the next.

Make no mistake, the introduction of CinemaScope was a critically important event in film history. It was the first viable weapon in the effort to get audiences back into theatres. Seen above is the special CinemaScope marquee mounted at the front of the courtyard at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood.

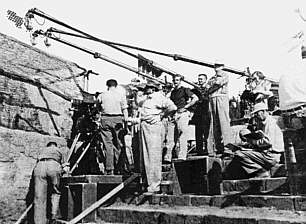

Photography of the first CinemaScope film in progress at the 20th Century Fox studios. The Director of Photography was Leon Shamroy, ASC. Note the live stereophonic sound recording.

(Left) The Robe director of photography Leon Shamroy, ASC (center) with Sol Halprin, ASC, Fox Camera Dept. head and Earl Sponable, studio research engineer look at one of the Chrétien anamorphoscope lenses used on the production. (Right) Another shot of the crew making the first CinemaScope film, again the three microphone booms show the live recording of the stereophonic soundtrack.

|

|

|

A somewhat exaggerated promotional picture advertising THE ROBE and CinemaScope. Note how the picture attempts to demonstrate CinemaScope’s similarity to both Cinerama and 3-D. And Fox weren’t by themselves in trying to equate CinemaScope to 3-D. Reviewers and optical gurus all around the world tried to explain how this new process could be 3-D without projecting two images and wearing glasses. Are you ready for this boys and girls? The explanation was that since the new CinemaScope screens were curved, (a really, really slight curve), each eye saw the image in a slightly different dimension, thus creating the three dimensional effect. Of course that’s absolute nonsense. The square made of broken lines is to demonstrate what the old screen looked like… Tool of marketing, Exaggerate more than a little.

A scene from the ROBE, photographed directly from the screen in a 20th Century Fox screening room in 1953. With an added sepia section in the center of the wide 2.66:1 image to show the standard 1.37:1 image as would be taken if the anamorphic lens was not used. The image on the CinemaScope film was taller as well as being wider than the Academy standard frame.

|

“The Modern Miracle you can see without glasses” Attempting to liken CinemaScope to 3-D while making a point of not having to wear uncomfortable cardboard glasses. Many early CinemaScope posters also publicized the system’s Full dimensional high fidelity stereophonic sound.

The opening moments of THE ROBE show the viewer that something special is about to happen. Beginning without Alfred Newman’s fanfare, rare since its introduction in 1935, the always impressive 20th Century-Fox logo and all following credits are laid out over gold trimmed wine colored drapes which will open to reveal the new breadth of the theatre screen, an obviously intentional attempt to emulate the massive curtain pullback seen in Cinerama.

BANNER ACROSS BOTTOM OF FRONT PAGE OF SEPTEMBER 24, 1953 HOLLYWOOD REPORTER The Robe opened in Los Angeles a week after it had premiered in New York and Chicago. The Roxy in New York recorded a world’s record gross in the first week.

How to Marry a Millionaire released on the coat tails of The Robe, it was begun after the latter and completed before it.

Fox had worked on The Robe for several years and they were intent that it would showcase CinemaScope’s introduction. For pure entertainment, those three girls were probably a better bet, but The robe had action sequences that overcame the static photography from which a number of the early productions suffered.

Also in production at the same time as The Robe and How to Marry a Millionaire was Beneath the 12-Mile Reef, all of which used original Chrétien lenses, (the only three deemed to be of adequate quality to be used). Had the film been produced in standard black and white it would probably have qualified as an above average “B” picture. With the beautiful Technicolor (Eastmancolor negative) CinemaScope photography, stereophonic sound, and an especially evocative music score by Bernard Herrmann, Beneath the 12-Mile Reef becomes an entertainment worthy of pulling audiences away from their televisions. Young Robert Wagner and gorgeous Terry Moore play the romantic leads and Gilbert Roland plays the same part that he played in dozens of films.

- Fox used its most powerful sales people to promote CinemaScope. Cinerama didn’t have Monroe, Paramount didn’t have Monroe, Fox had Monroe and she was in CinemaScope. Did she contribute to the success of Fox’s wide screen system over the competition? Most likely, the answer is yes. At right, Marilyn is seen fondling a Bausch & Lomb Type I CinemaScope projection lens, which sold for over $2,800 per pair at a time when homes sold for $5,000.

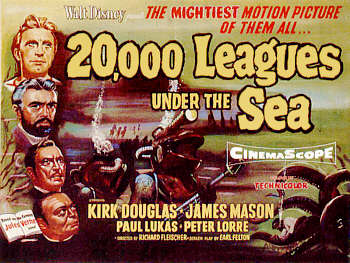

One of the earliest, and best, examples of CinemaScope, Walt Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea (1954). Had the CinemaScope’s original 2.66:1 aspect ratio was reduced to 2.55:1. The squarer “FoxHole” sprocket holes were used to allow for slightly wider magnetic stripes than the conventional Kodak or Bell & Howell sprocket holes would allow. The narrow track carried the effects channel sound. Control tones turned the auditorium amplifiers on and off as required because the narrow track tended to be “hissy” when no sound was present.

The anamorphic camera adapters were in such short supply when this and all the other early CinemaScope films were made that each production was allocated a single lens. If a second lens was absolutely necessary it would be dispatched by motorcycle courier from the 20th Century Fox camera department.

The circle in front of the camera is the Bausch & Lomb CinemaScope adapter lens during the filming of 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea.

CinemaScope may not have been a critical part of the production but it forever makes it a contemporary film with quality wide screen camera work and marvelous four track stereophonic sound. No amount of CGI could have improved what the Disney team pulled off in 1954.

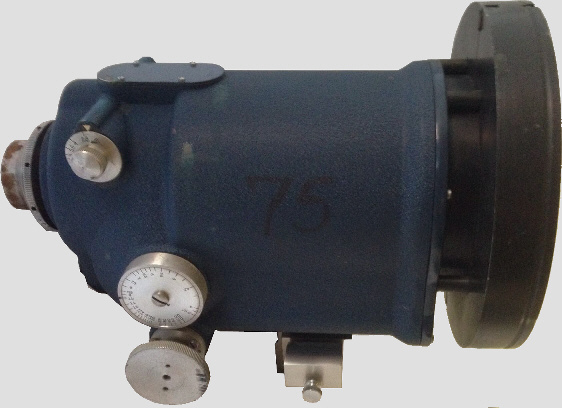

Current photo of a vintage Bausch & Lomb CinemaScope adapter lens, (20th Century-Fox camera department inventory number 20-181), courtesy of John Whittle.

While the adapter was superceded by the “combination” lens in 1954, they continued to be used throughout the life of CinemaScope production. Due to the small diameter of the rear element, the adapter was useable with only a few focal lengths of the Baltar prime lens. It was necessary to focus the adapter and the prime lens separately, considered to be a significant drawback when focus was changed during a shot.

Hedging Bets – Seen at left is an Australian poster for Knights of the Round Table. MGM produced both CinemaScope and conventional “flat” versions of this film and quite a few others during the first months of the new anamorphic revolution. Fox had done the same only with The Robe. While these conventional versions were seldom, if ever, seen in North America, they did get some play in Europe before an adequate supply of anamorphic projection lenses was available and enough theatres had installed the new wide screens. Despite not being in CinemaScope, this version of Knights of the Round Table was also in Color Magnificence. Quite likely Technicolor made the European prints at that time.

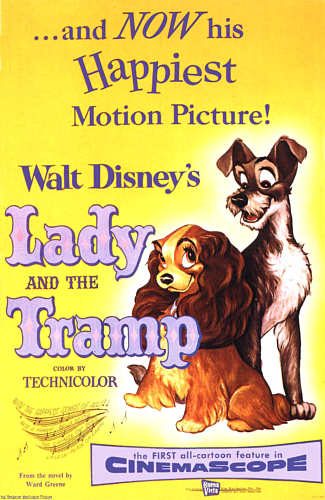

Walt Disney put his animators to work immediately using the new CinemaScope process and created the first animated cartoon in the system, Toot, Whistle, Plunk, and Boom. He also produced the first feature length cartoon, Lady and the Tramp. Like MGM, Disney also hedged his bets on CinemaScope, he had the film photographed in standard Academy format for theatres that did not install the new system. By the time the film was finished, in 1955, CinemaScope had been so universally accepted that the Academy version remained virtually unseen for decades.

Lady was virtually complete when Walt Disney decided have the film reshot in CinemaScope. Rather than taking in a wider image than normal, the rephotographed Lady and the Tramp retained the same width in CinemaScope as the original flat photography but substantially less tall.

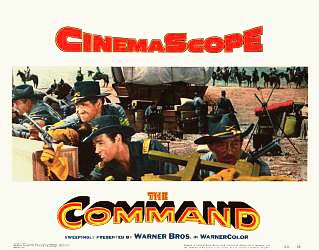

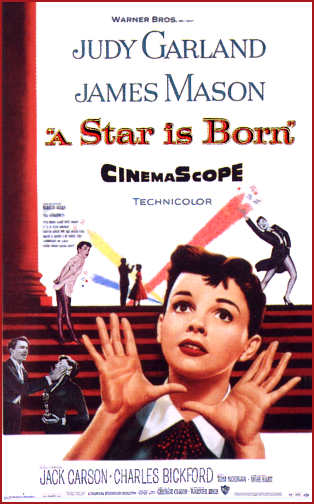

Warner Bros. first real CinemaScope feature was the remake of Selznick’s A Star Is Born. The studio had first produced a film called The Command hoping to use Zeiss anamorphic lenses. Warner’s had a contract with Zeiss but they had problems and Warners used Vistarama optics, manufactured by the Simpson Optical Manufacturing Company. The Zeiss camera lens problems appeared insurmountable and Warner’s finally signed a contract with Fox for the use of CinemaScope and Bausch & Lomb optics. As part of the agreement, The Command was released under the CinemaScope banner rather than the failed WarnerSuperScope moniker. Fox bought out Warner’s lens contract with Zeiss and put the German lens maker to work improving their design for projection lenses, which were in short supply.

A Star Is Born, which was a truly big budget film, directed by George Cukor, was given enough money to let Technicolor do the lab work and printing.

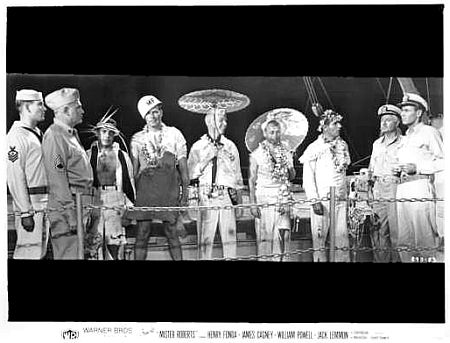

Typical publicity still from Warner Bros. during the early CinemaScope era. Jack Warner may have had some bruised feelings after his short widescreen battle with Darryl Zanuck, but when he used CinemaScope he publicized it extensively. The only problem with Warner’s CinemaScope pictures was the fact that they continued to use their own WarnerColor lab for several years, sending out the worst looking prints in the history of motion pictures. By the mid-50s, Warner’s shut down their lab and went exclusively with Technicolor. The difference in the look of Warner product was very obvious, with the studio releasing some of the best looking films to come out of the Hollywood studios during the last decade and a half of dye transfer Technicolor.

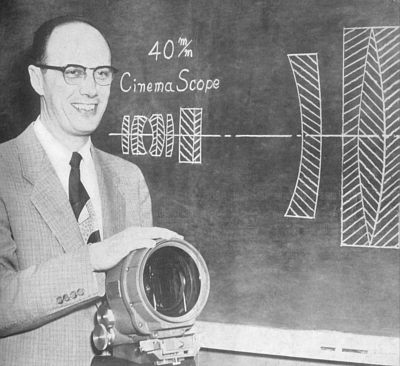

Shown against a blackboard diagram of a new 40mm CinemaScope camera lens is John D. Hayes, head of the photographic department of Bausch & Lomb Optical Co. He holds the first of the new CinemaScope lenses, shipped recently to 20th Century-Fox. The complex 12 element lens was developed under Hayes' direction. The 40mm lens is first of a complete range of focal lengths up to 152mm now under development. Its attributes include improved resolving power, much less distortion, enhanced definition and improved color correction. (Cover photo and caption from July, 1954 AMERICAN CINEMATOGRAPHER) The lens being fondled by Mr. Hayes is a 50mm CinemaScope combo rig, not a 40mm as is described.

The next step in the evolution of CinemaScope was the development by Bausch & Lomb of the “combination” lens. These lenses eliminated the use of a separate adapter and prime camera lens, allowing for improved optical characteristics as well as making lens focusing simpler. This lens below, from the WideScreen Museum optics collection, is a 40mm model adapted with a special low vibration mount. It dates from the developmental period in 1954 and saw use on many productions at Fox and later at Warner Bros. The Bausch & Lomb lenses had iris and focus knobs on both sides of the lens, making life easier for camera assistants. On both sides of this lens can be seen the focus puller’s hand written scales mounted around the engraved scales. The hand written scales allowed markings to be made at specific distances required for a particular shot. The front element is 8 inches in diameter and the lens weighs approximately 10 pounds. Bausch & Lomb 40mm CinemaScope combination lens from the museum collection. The lens has been modified with a special anti-vibration mount.

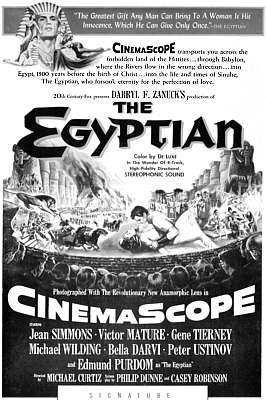

Poster for The Egyptian. A three quarter page newspaper ad, announcing the first film to use the redesigned B&L CinemaScope lenses. Below: Detail from the ad.

20th Century-Fox obviously thought that the public would like to know that the process had been improved. They continued to use Cinerama-style graphics to show the viewer involvement in CinemaScope films. Seen below is a newspaper article from The Egyptianpress book, designed for theatres to “plant”. Darryl F. Zanuck’s “The Egyptian,” which brings to vivid cinematic life the turbulent drama of ancient Egypt, is the first important motion picture conceived along spectacular lines to reveal the breathtaking results of CinemaScope’s advancing techniques.

In a little more than a year since CinemaScope was introduced with “The Robe” and revolutionized the standards of the motion picture industry added values have been brought to the anamorphic wide-screen process. The optical firm of Bausch and Lomb improved on the original lenses of Professor Henri Chrétien, inventor of the anamorphic process, and developed a series of camera lenses that give CinemaScope greater flexibility, range and depth.

These newly-perfected lenses were used to photograph “The Egyptian” and they gave to the production a greater clarity of image and a new sense of intensified audience participation than had heretofore been achieved. They opened up new vistas of entertainment for the public with better relative definition over the entire surface of the large screen. With the new lenses the cinematographer has greater maneuverability for his cameras to give finer pictorial qualities and the director wider latitude in which to achieve added dramatic values. CinemaScope, which achieved instant public acceptance when it was introduced, now gives greater entertainment values.

In addition to “The Egyptian,” many other top attractions will come from Twentieth Century-Fox in the months ahead, all reflecting the advancing techniques of CinemaScope. Among them are “Woman’s World,” with an all-star cast including Clifton Webb, June Allyson Cornel Wilde, Fred MacMurray, Lauren Bacall, Van Heflin, and Arlene Dahl; Oscar Hammerstein’s Broadway hit, “Carmen Jones”; Marlon Brando as Napoleon and Jean Simmons in “Desiree,” also starring Merle Oberon and Michael Rennie.

Also, Irving Berlin’s “There’s No Business Like Show Business,” the most costly musical of all time, starring Ethel Merman, Donald O’Connor, Marilyn Monroe, Dan Dailey, Johnnie Ray and Mitzi Gaynor, “Black Widow,” starring Ginger Rogers, Gene Tierney, Van Heflin and George Raft; Tyrone Power and Susan Hayward in “Untamed,” filmed in South Africa, and Kirk Douglas and Bella Darvi in “The Racers.”

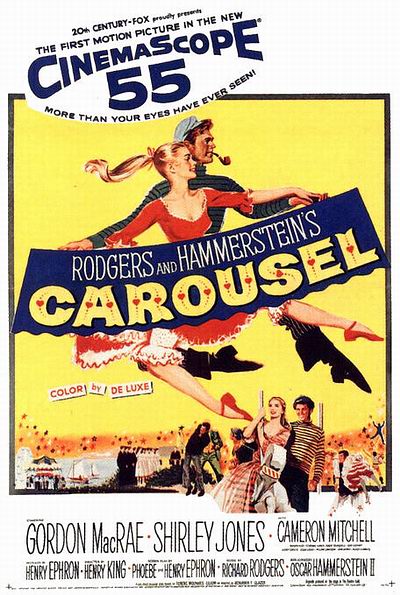

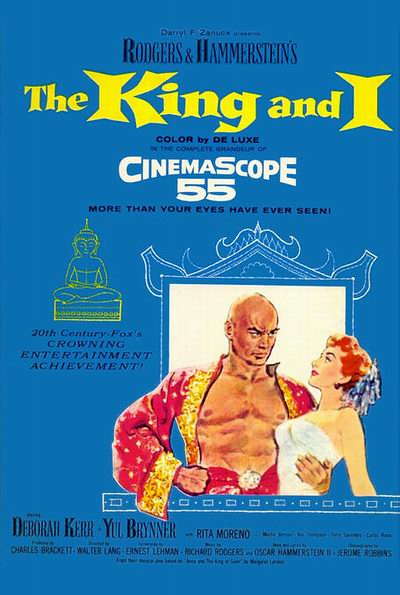

Also, Richard Burton as Edwin Booth in “Prince of Players”, James Stewart and Jane Russell in “Jewel of Bengal”, Fred Astaire and Leslie Caron in a new musical version of “Daddy Long Legs”, Marilyn Monroe in “The Seven-Year Itch”, Sheree North in “Pink Tights”; Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “The King And I”; Cole Porter’s and Abe Burrows’ sensational Broadway musical success, “Can-Can”, “A Many Splendoured Thing,” and Fulton Oursler’s “The Greatest Story Ever Told.”

The policy of Twentieth Century-Fox will be to maintain and constantly improve the medium of CinemaScope, so that it will remain the undisputed leader in motion picture entertainment. Such is the credo of the film company’s president Spyros P. Skouras.

Combination “Magoptical” sound The Man Who Never Was (left) and standard optical mono sound Ferry To Hong Kong (right).

Though 1952 – 1953 the major studios had believed that multi-channel stereophonic sound would become a standard that would replace optical mono. Theatre operators resisted the heavy expenditures for the new sound systems and lobbied for the availability of optical sound on CinemaScope films. 20th Century Fox balked at the use of optical sound with CinemaScope but other studios came up with a combination “Magoptical” print that carried a half width mono track in addition to the four magnetic sound tracks. Fox finally relented and adopted the magoptical sound track as well. The addition of the optical sound track reduced the width of the image and an aspect ratio of 2.35:1 was adopted for all but magnetic only films.

Eventually standard mono sound became the norm with stereo being run by major first run theatres. Without the magnetic tracks on the film it was not necessary to use the smaller “Fox Hole” sprocket holes. From 1954 through 1957 many M-G-M, Paramount, Universal, and Warner Bros. film used Perspecta optical directional sound, (it’s an out and out lie to call it stereophonic). See the VistaVision wing and the Technical Library section for substantial information on Perspecta Sound.

Until 1959, Fox reserved the CinemaScope name only for “A” budget films, which were substantially all in Color by DeLuxe. Starting in 1957, what might be classed as “A-” films would sometimes be photographed in black & white. They might be “B” quality but Fox didn’t treat them that way. Genuine low budget, or “B” films, did not carry a Fox banner. Instead they were produced for Fox by Regal Films and while the lenses were still the same Bausch & Lomb CinemaScope optics, the process was labeled Regalscope. Ultimately the company released a number of prestige films in CinemaScope and black & white, including The Diary of Anne Frank, The Longest Day, and Sink the Bismark!. Any film starring Peggy Castle couldn’t be considered anything less that a class A attraction. That is the unanimous opinion of the staff and management of The American WideScreen Museum.

The Curator admits a weakness for the pretty women, and no actress in the film industry ever carried the combination of beauty and dignity better than Olivia deHavilland. Seen here is Olivia and John Forsythe in The Ambassador’s Daughter, produced independently in Paris in 1956. The image is taken directly from a yummy Technicolor dye transfer print.

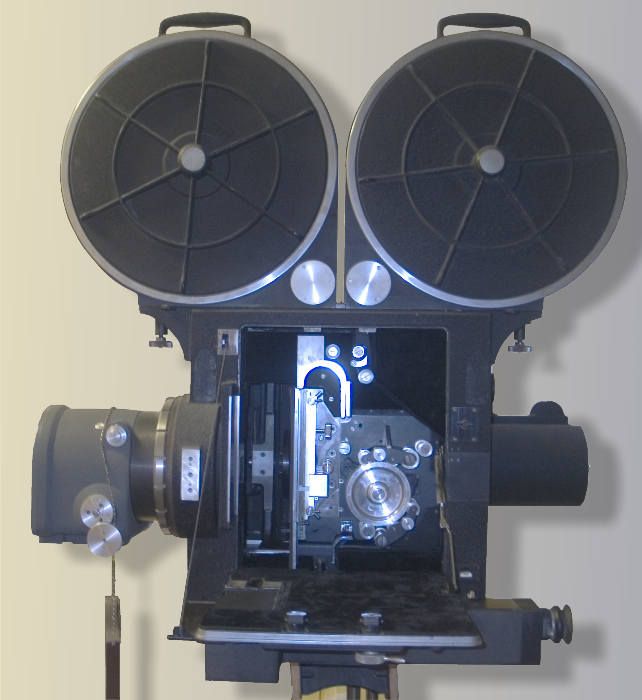

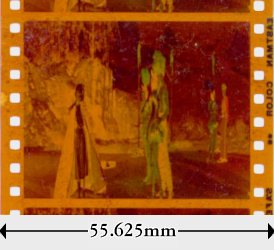

Sol Halprin, A.S.C. (second from left), 20th Century Fox Executive Director of Photography, Grover Laube (left), studio engineer, and Earl Sponable, Chief Research Engineer, not shown, developed the large format CinemaScope 55 system. The camera is the Fox 4×55, a Mitchell 70mm camera built circa 1930 and converted by the Fox camera department to handle the 55.625mm Eastman negative. Fox initially had to handle the slitting and perforation of the negative in their own laboratory. Eastman Kodak soon produced the necessary film for the process in the requisite dimensions and perforations. Both the negative and the planned 55mm print used the small “FOX HOLE” perforations developed for the 35mm version of CinemaScope.

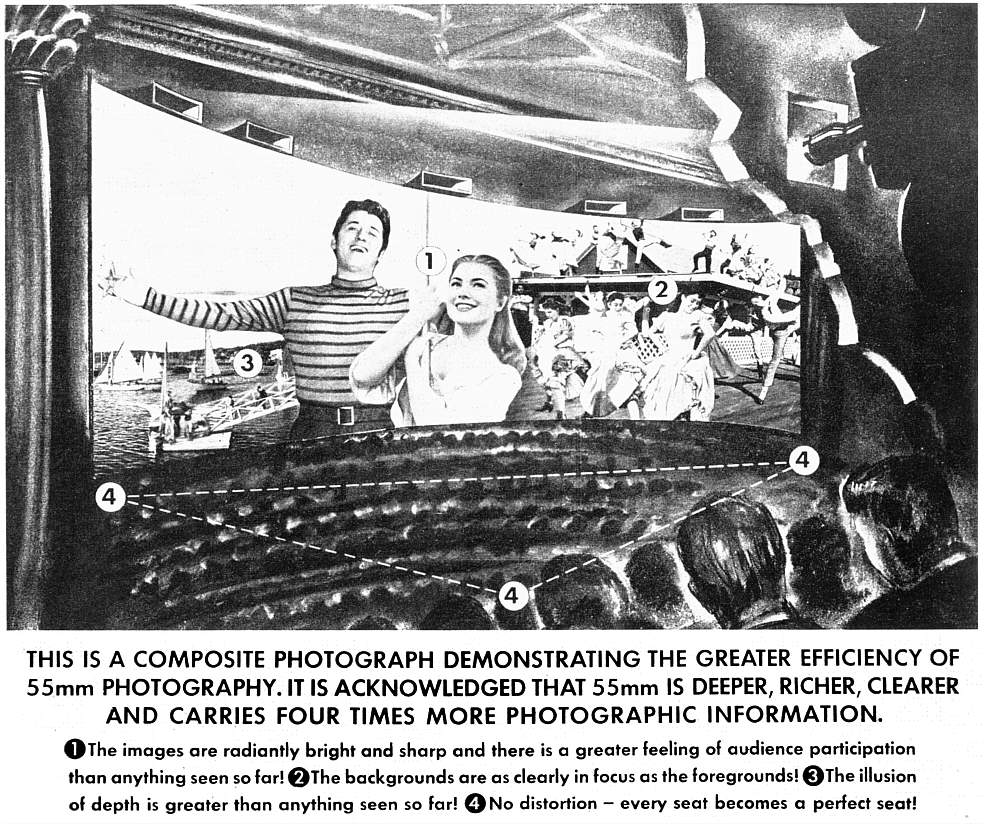

Below: A couple of CinemaScope 55 promotional images created for exhibitors to tout the quality of the new system and encourage the installation of full four track magnetic stereophonic sound where it had been resisted up to that time. Fox declared that CinemaScope 55 films would be released only with magnetic sound. Fox derived very little income from the installation of magnetic stereo in theatres. They had an operating division that could provide CinemaScope gear but there were many sources for the necessary penthouse sound playback gear, amplifiers, and speakers. Fox was genuinely attempting to associate quality presentation with the CinemaScope name.

The aspect ratio may be exaggerated substantially, a tradition in CinemaScope promo artwork. The display of five screen speakers was almost a red herring as only two or three theatres ever ran an interlocked six track magnetic film with the two features produced in the system. Virtually all theatres relied on the four track sound, with three screen channels, that were applied to the projection print.

With just one camera modified to 55mm, the studio began production of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s “Carousel” in Boothbay Harbor, Maine. Initially filming was done in both 55mm and 35mm CinemaScope. The 35mm version was shortly abandoned as studio chiefs gained confidence in the larger format system.

The image quality of CinemaScope 55 was better than the artwork commissioned to introduce it. Unfortunately, the public didn’t perceive much difference between CinemaScope and its large format brother, no doubt due in part by Fox’ marketing methods. Newman’s fanfare music for CinemaScope probably helped confuse the differences between the 35mm and 55mm formats in the minds of patrons. It is also quite possible that the image quality of the prints made by DeLuxe Labs did not fully convey the superiority of the large negative. (See Note on Technicolor, below)

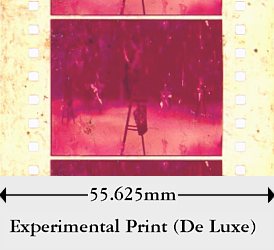

Surviving samples of CinemaScope 55 negative and an experimental 55mm print without the six magnetic soundtracks. Both samples are from Carousel. No 55mm theatrical release prints were planned for that film.

While the camera negative was 8 perforations high, the planned 55mm print would be reduction printed to just 6 perforations. This allowed room for six magnetic sound tracks. Ultimately neither Carousel no The King and I, were ever shown in 55mm, and no record of a 55mm print exists. Instead they were both reduction printed as standard 35mm CinemaScope. The use of the larger negative, even after being reduced to 35mm, resulted in a claimed 50% improvement in clarity and definition. After The King and Iin 1956, 20th Century Fox abandoned CinemaScope 55 in favor of doing their large format productions in Todd-AO, in which they acquired a financial interest. While comparing the frame area to other large format systems might lead one to believe that CinemaScope 55 would offer the best image of the lot, this probably was not true. The optics were much more complex than Todd-AO and suffered the same drawbacks as those used in conventional 35mm CinemaScope. Fox’s decision to adopt Todd-AO can be considered a strong indication that working with the large CinemaScope 55 anamorphic system was difficult and, quite likely, more costly than the 65mm/70mm format.

It is interesting to note that many of the first release prints of The King and I were made by Technicolor in their dye transfer process even though no screen credit is given. It is quite possible that the Technicolor process preserved the image quality of the large format negative much better than the Eastmancolor prints produced by Fox’s own DeLuxe Labs. Similarly, M-G-M had Technicolor make the 35mm anamorphic prints for their first large format production, Raintree County, filmed in Ultra Panavision 70 in 1957.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

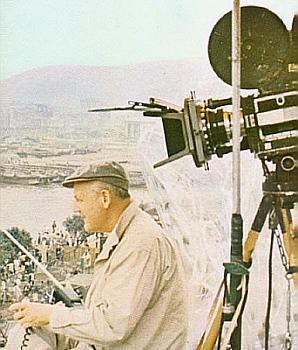

Daryll F. Zanuck wearing an unofficial director’s hat in addition to his official position as producer of The Longest Day, in CinemaScope, the most expensi

ve black and white film made until Schindler’s List three and a half decades later. Zanuck was a true icon in the film industry, driving 20th Century-Fox through their most productive and successful years. We’ll let Mr. Zanuck wear whatever hat he wants while we take ours off to him.The pioneering work on anamorphic 35mm widescreen spearheaded by 20th Century Fox president Spyros Skouras, vice president Darryl F. Zanuck, and their technical staff set the standards by which all similar systems conform up to this day.

Throughout the 1950’s other studios adopted CinemaScope compatible widescreen systems. Little Republic Pictures bought a fistful of anamorphic lens

es in France and produced “Naturama” films. Warner Bros. likewise acquired anamorphic lenses and released several pictures in “Warnerscope”. Even 20th Century Fox, who had stated that all CinemaScope pictures would be photographed in color, made several in black and white and called them “RegalScope”. Later they would revert back to the CinemaScope trade name even for black and white.

A small company by the name of Panavision began producing anamorphic projection lenses in the early 1950’s to meet the demand as more and more theatres adopted the CinemaScope format. A close relationship with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer brought them into the business of designing camera optics and ultimately cameras. A vastly improved CinemaScope lens was awarded an Oscar and gradually found its way into the production of more and more films. While Fox still licensed the use of the CinemaScope trade name, MGM and other studios adopted the Panavision lenses over the last part of the decade.

Ultimately, as more and more studios closed down their in house camera departments, the Panavision lens and cameras came to the forefront. In 1967, 20th Century Fox abandoned the use of their Bausch & Lomb CinemaScope lenses and began using Panavision for their anamorphic films.

One of the last films to carry the goose bump raising CinemaScope logo, Stagecoach, produced by Martin Rackin and directed by Gordon Douglas in 1966, featured a star studded cast but it pretty well fizzled. On its own it might have been more favorably reviewed but being a CinemaScope – Color by DeLuxe – Stereophonic Sound remake of a screen classic, it just didn’t cut the mustard.

END OF AN ERA

Too late to improve the “Mumps” reputation. The Bausch & Lomb Blue Series “E” lenses corrected for the non-linear compression at close distances that had created the “CinemaScope Mumps” reputation. The elliptical bathtub looking component on top of the lenses housed a mechanism that performed the same basic function as Panavision’s Auto Panatar lenses did, but without violating Robert Gottschalk’s patent of counter-rotating “astigmatizers”. This change was instigated in the mid 1960s and it’s unknown how many lenses went through this modification.

In 1967 the curtain rang down on the trusty Bausch & Lomb CinemaScope lenses after the completion of a pair of “spy thrillers”In Like Flint, a typically amusing romp with charismatic James Coburn in the title role of an American secret agent, and Caprice, starring Richard Harris and breathy Doris Day in a suitably forgettable picture. While Flint was no great competition to Sean Connery’s James Bond, he was a lot more entertaining and funny than Dean Martin ruining the Matt Helm series over at Columbia. As for Caprice, it was no great competition for any film and its sole distinguishing element is that it was the final film to be released as a 20th Century-Fox CinemaScope Picture.

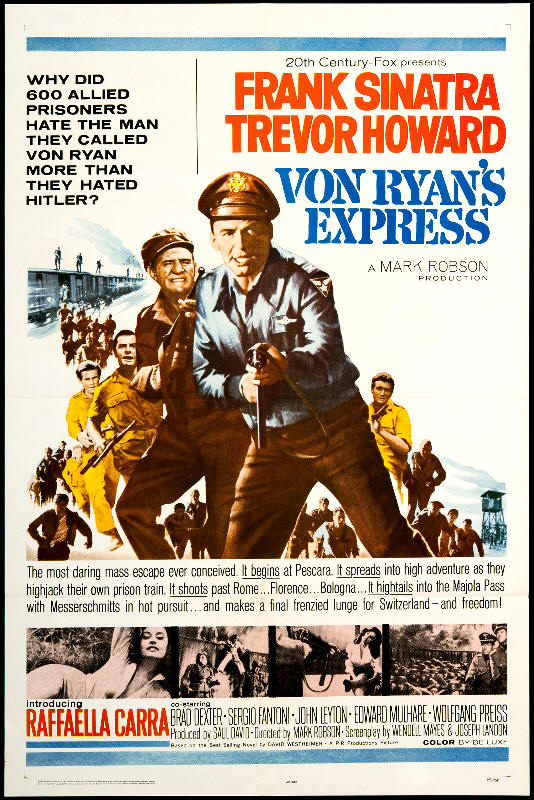

The most enigmatic of all CinemaScope films. You may note that there is no mention of CinemaScope on the poster. While listed as a CinemaScope production, we’re told that star Frank Sinatra insisted on the use of Panavision lenses, at least for his scenes

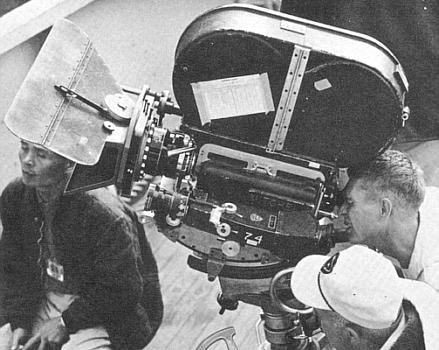

At left, Robert Wise directing The Sand Pebbles in Taiwan, one of 20th Century-Fox’s first Panavision films. The film was initially released in road show presentations. At right, Steve McQueen peering through the lens of a Mitchell BNC fitted with Panavision, rather than Bausch & Lomb anamorphic optics.

In 1957, Panavision Inc. introduced the Auto Panatar compact anamorphic lens, which ultimately became the de-facto standard in high quality motion picture optics.

Film historian Rick Mitchell, who has heavily researched the subject, provides us with a bit more insight into Fox’s move from CinemaScope to Panavision: “While THE SAND PEBBLES may have been the first film credited to Panavision to go into production, the first to be released was the Parisian made HOW TO STEAL A MILLION, which opened in the summer of 1966. However, according to sources at Panavision, most of the principal photography on VON RYAN’S EXPRESS (1965) was shot with Panavision lenses at the insistence of Frank Sinatra, who, along with John Wayne, had been a big booster of Panavision. (The Sinatra co-produced A HOLE IN THE HEAD (1959) was the first 35mm feature to be solely credited to Panavision.) A close examination of a 16mm anamorphic print of VON RYAN reveals some shots that have ‘anamorphic mumps’ but all the scenes with Sinatra look like films shot with Panavision lenses in the same period.”

As Rick points out, William Wyler’s How To Steal A Million was the first Fox production to be released carrying a ‘Filmed in Panavision’ credit. The film starred Peter O’Toole and Audrey Hepburn. By a not too surprising coincidence, Hepburn happened to appear in MGM’s Green Mansions, (1959), which is frequently referred to as that studio’s first picture shot with Panavision optics. However, other films are sometimes credited as MGM’s first use of Panavision, including Jailhouse Rock, (1957), the Elvis Presley ‘classic’ shot in black & white. But even though Jailhouse Rock carried both CinemaScope and Panavision credits, it was actually not photographed in either widescreen system. It would have been more correct to say it was a Superscope production since the image didn’t become anamorphic until the prints were made through Panavision’s MicroPanatar printer lens. Seen below are credits from the film. “Process Lenses by Panavision” indicates that anamorphic printer lenses were used to make CinemaScope compatible show prints. For anamorphic photography the credit would say “Photographic Lenses by Panavision”.

While the major studios began to adopt Panavision for their anamorphic films, the trusty old Bausch & Lomb CinemaScope lenses didn’t disappear. They gradually made their way into the hands of independent film makers and continue to be used to this day.